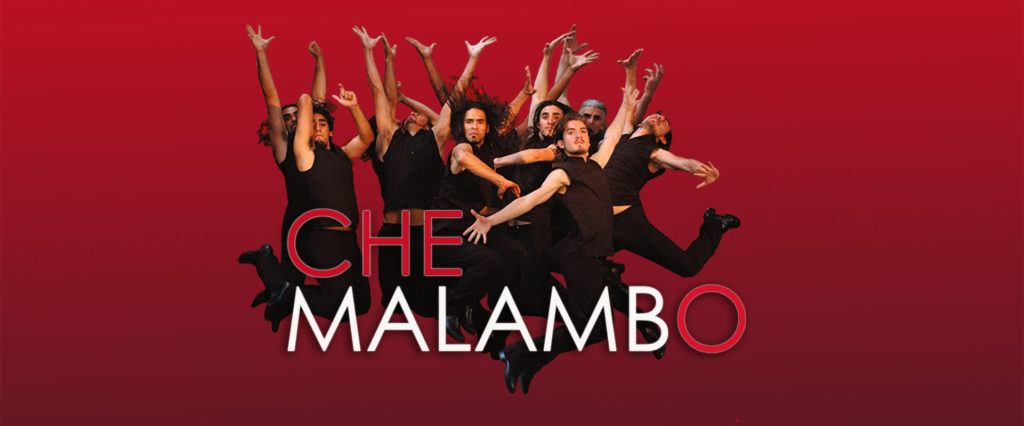

Che Malambo Returns to Paris with Dueling, Dancing, and Drumming

Che Malambo brought the sounds of galloping horses and the heart of the gaucho to the Bobino Theater this past weekend, paying homage to the South American cowboy through passion, strength, and dances with danger.

The greatest Malambo dancers in Buenos Aires and beyond, some training in the Argentinian dance since they were eight years old, were gathered to form Che Malambo under the direction and choreography of Gilles Brinas. While the group has toured in more than 32 countries, Brinas is originally from Paris and the group first premiered in Paris in 2007, giving this city a special tie to the group. The company has returned to Paris this season until April 21 for viewers to witness a new season of music, dueling, and celebration.

Before there was dancing, there was drumming–the curtain opened to a percussive thunder, all 12 men with stern faces and stiff muscles that have been working for more than a year to perfect this performance.

They began a fierce rhythm on South American bombos that captured the audience’s applause before their shoes even began to tap–it first appeared to be more of a drum concert than a dance concert. But when their feet began their furious and musical movement, their sticks twirled in unison across the drums, and their cries echoed from the back of the auditorium, it was clear that every part of this dance was choreographed just as much audibly as it was visually.

However, this performance is not for those who seek a relaxing day to sit back in their seats. Barely breaking for applause, the group was in nearly constant motion, each number seeking to outdo the last, reminding the audience what this dance truly was–a duel.

In the gaucho tradition dating back to the 17th century, Malambo was a challenge from one cowboy to another, a test of strength, of agility, of manliness. New challengers emerged on the stage, the fierceness in their eyes matching the fire in their feet. They danced alone, in pairs, and in unison, quickening their feet and passing the passionate baton from one gaucho to another until all dancers were nearly a blur from the waist down.

The dancers created music with every step and with every part of their shoes. With eyes closed, one would think galloping horses were seizing the stage (although we don’t recommend closing your eyes; the duel is too much to miss). The men created a chorus of galloping horses in unison, revealing the depth of brilliance of Brinas: when creating the choreography, he was simultaneously composing the score. Music and aesthetics were inseparable, and even the silence worked to the advantage of the dance and its tension.

The tension and danger seemed to be at their greatest. Then the boleadoras were brought to the stage.

These long cords with weights on each end were traditionally used as weapons, but on stage they were twirled until they were lasso-like blurs rhythmically clacking against the ground to create yet another form of accompaniment to this dance.

By the final curtain, boleadoras had been twirled over and under every dancer, behind backs, and twirled with teeth. The music from the boleadoras, drums, and tapping shoes mixed with the whistles and claps the audience could not restrain.

But as in all duels, there had to be a victor. The audience seemed to believe it was them.

The duel on stage ended suddenly, as the dancers snapped into smiles and began a new segment of dance, one of seeming celebration. Feet were still moving ferociously, but the aggressive cries were replaced with ones of cheer. The dance took an entirely new tone, one that almost let the audience relax into the backs of their seats.

While the dance followed several changes of pace, from dances in bare feet to a Spanish serenade on the guitar and even to the rare bit of humor on stage, the strength of the gaucho was never neglected.

Perhaps this is why the dancers gave an encore after their bow. And then another. And then another. Regardless, the applause and whistles lasted far beyond the final encore, and their bravado earned a bravo.

Visuels: ©Visuels Officiels